I first learnt of the Broomway when I read The Old Ways by Robert Macfarlane a few years ago. Since then I’ve always wanted to walk ‘the deadliest path in Britain’. The path stretches six miles from Great Wakering to Foulness Island across Maplin sands. Only accessible at low tide, the Broomway was the only way on and off the island until 1922. It has claimed more than 100 lives over the centuries. Today, Foulness island is owned by the Ministry of Defence, meaning that the Broomway can only be walked in good visibility and on days when munitions aren’t being tested. As soon as you reach Foulness you must turn around and walk back again.

Down the pub, I mentioned all this to the boldly goes trio and was pleasantly surprised when they invited me to walk it with them. Given the path’s fearsome reputation we made sure to do our homework. This meant encountering the story of a young man who, poaching for wildfowl one January afternoon with friends in 1969, never returned from the sands after a thick mist rolled in quickly from the North Sea. Sudden fog was definitely our main concern and we made sure to take a second compass just in case we would need to ‘steer’ ourselves back to safety. I even went out the evening before our trip to practice navigating quickly and accurately in the half-light.

On the morning of the walk we got up early and made the drive from Hertfordshire to Great Wakering in order to arrive with plenty of time to explore the Broomway before the tide turned. The forecast was good but it was an icy November morning and we were still anxious that the whole trip may yet come to nothing.

It turns out that just before you reach Wakering Stairs there’s a military checkpoint that also controls access to the Island. After asking nicely, we were allowed to drive through and park at the start of the Broomway itself. It was cold and slightly foggy, a typical North Sea morning. Less typical were the warning signs and the squat grey watchtower staring out over the tundra-like sands towards the mouth of the Thames. Visibility wasn’t great, but it wasn’t bad either, and we’d come a long way so we headed down the slipway and onto the sands.

You can’t actually see the destination of Foulness Island for the first few hundred yards. The Broomway heads straight out to sea. Remnants of one or two of the brooms that gave the path its name, driven into the mud centuries ago to mark a safe route, still survive. This, combined with a sea mist, the sound of geese and a distant foghorn, make those first few hundred yards amongst the most surreal experiences I’ve ever had walking in the UK.

It isn’t hard to see why Maplin Sands were once earmarked for a new London airport. They are completely flat and, as we walked away from the shore, the final inches of the old tide rushed out over our boots. Looking down was surprisingly disorientating but, luckily, the fog was beginning to lift. At this point we realised that the Broomway isn’t all that long, and that the sands didn’t appear to be a complete death trap after all. This was partly a disappointment, but it did mean that we decided to wander out to an old shipwreck visible beyond the official path.

Distances are quite hard to judge on a featureless mudflat, and unsurprisingly the shipwreck was further away than it looked. Nevertheless, it didn’t take long until we were tentatively testing the sand inside the hull (definitely unsafe) and marvelling at the size of the oysters encrusted to the wood. From the shipwreck we deviated completely from the official path, instead following a line directly between two large posts that mark the river mouth of Havengore Creek for the benefit of sailors.

Sometime after reaching the second post we headed for Foulness Island itself. We aimed for Asplins Head, one of only two slipways to the island that are still in use. At the time I thought this seemed unnecessary. After all, there wasn’t anything special about Wakering stairs, we’d simply walked down onto the sands, why couldn’t we simply walk back to shore wherever we wanted?

There turned out to be a very good reason for not simply ignoring the map and making for shore. It turns out that the Foulness shoreline is a salt marsh. Any attempt to make it to dry land sooner than Asplins Head would involve slogging through knee deep mud (at best!). You would not want to be making for Foulness Island in a thick fog with the tide at your back!

Walking up onto the Island at Asplins Head, which still involves plenty of mud and a surprising amount of wild samphire, you’re greeted by another set of warning signs and a broad view of the island. Being flat and rural it looks, at first glance, like much of England. But the fact that entry is explicitly forbidden, and the fact that you can’t see the village itself from the headway, gives the whole place a deserted and desolate feel. It reminded me of the 1960s British TV show “The Prisoner” and I half expected Rover to come bounding across the fields toward us.

After absolutely no forbidden photographs (and definitely no trespassing) we decided to head back. The mist was gone and the sands looked just as strange in the bright sunlight. Everything looked like a watercolour. Giant container ships bound for the Thames glided over a thin plane of shimmering glass between the sand and the sky as we made for the flat greeny-brown smudge of Essex.

I can honestly say that the Broomway is one of the strangest places I’ve walked in the UK. And despite the fact that Maplin sands did turn out to be a little less dangerous and a little more like a giant beach than I was expecting, I still want more. I want to walk out further and reach the Sea. I want to visit at high tide in James’ boat and I want to keep walking past Aplins head along the shore of Foulness Island. Above all I desperately want to come back and walk the Broomway at night. I’ve no doubt this this would definitely be quite dangerous but I know that it will make the sands seems even larger, even stranger, even more desolate than they already are.

Walking the Broomway also makes me think… what other tidal adventures are to be had in the UK? Well… I have some ideas already and I certainly plan on bringing them up next time in the pub with the Boldy Goes Trio.

Tips for walking the Broomway:

-

Wellington boots are recommended. The water will easily swamp hiking boots and whilst bare feet would be fine away from the shore you do need something sturdier for Wakering stairs ands for making your way onto Foulness Island.

-

Make sure to do your research, especially around tide times. Consult David Quentin’s Broomway website.

-

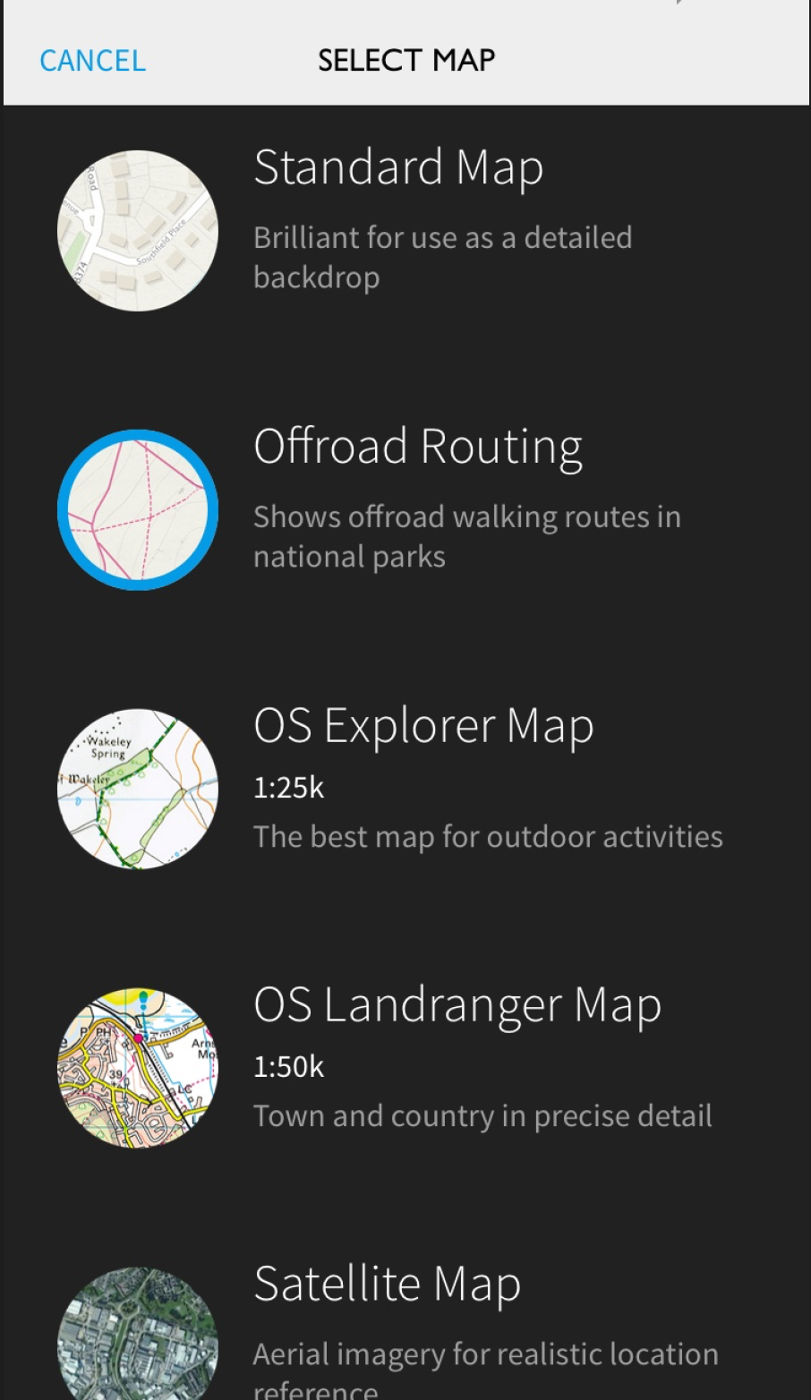

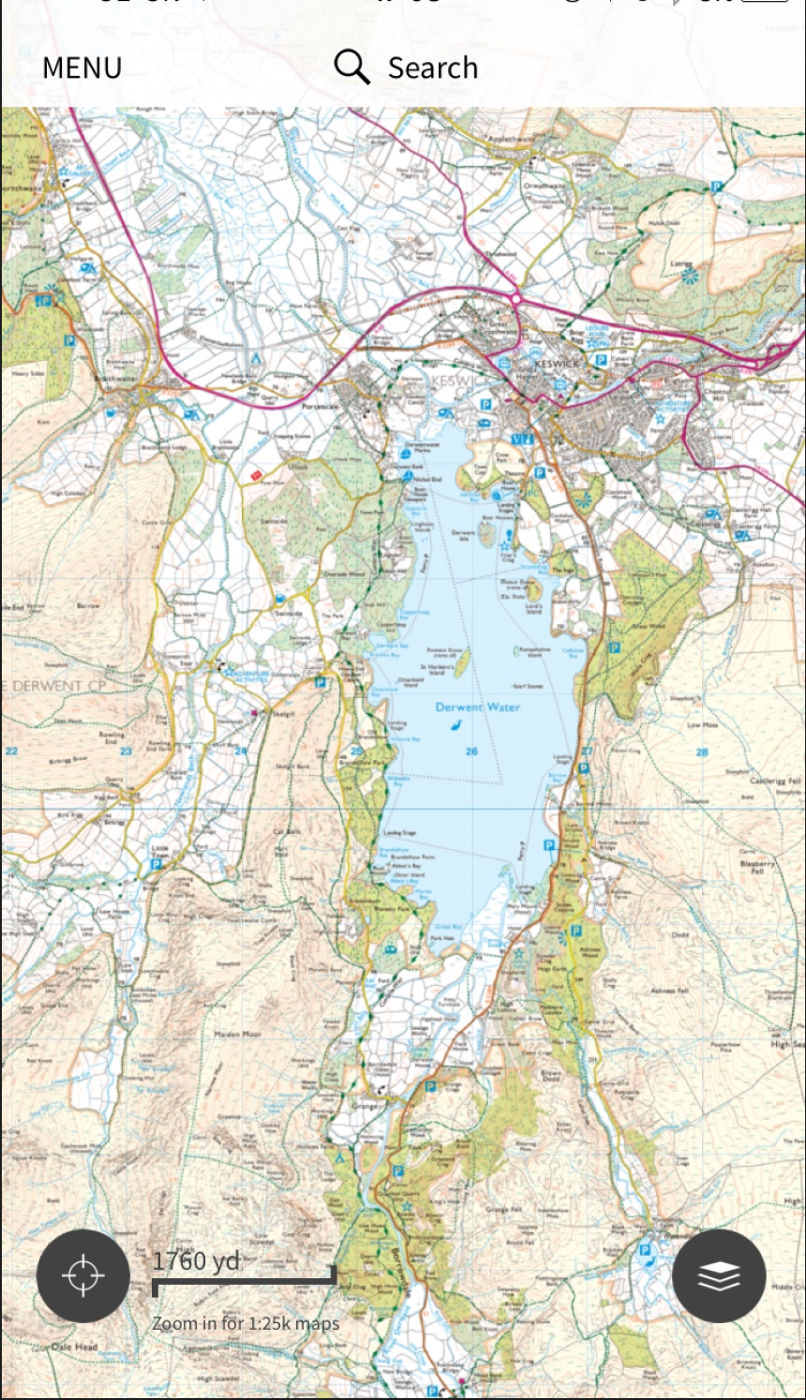

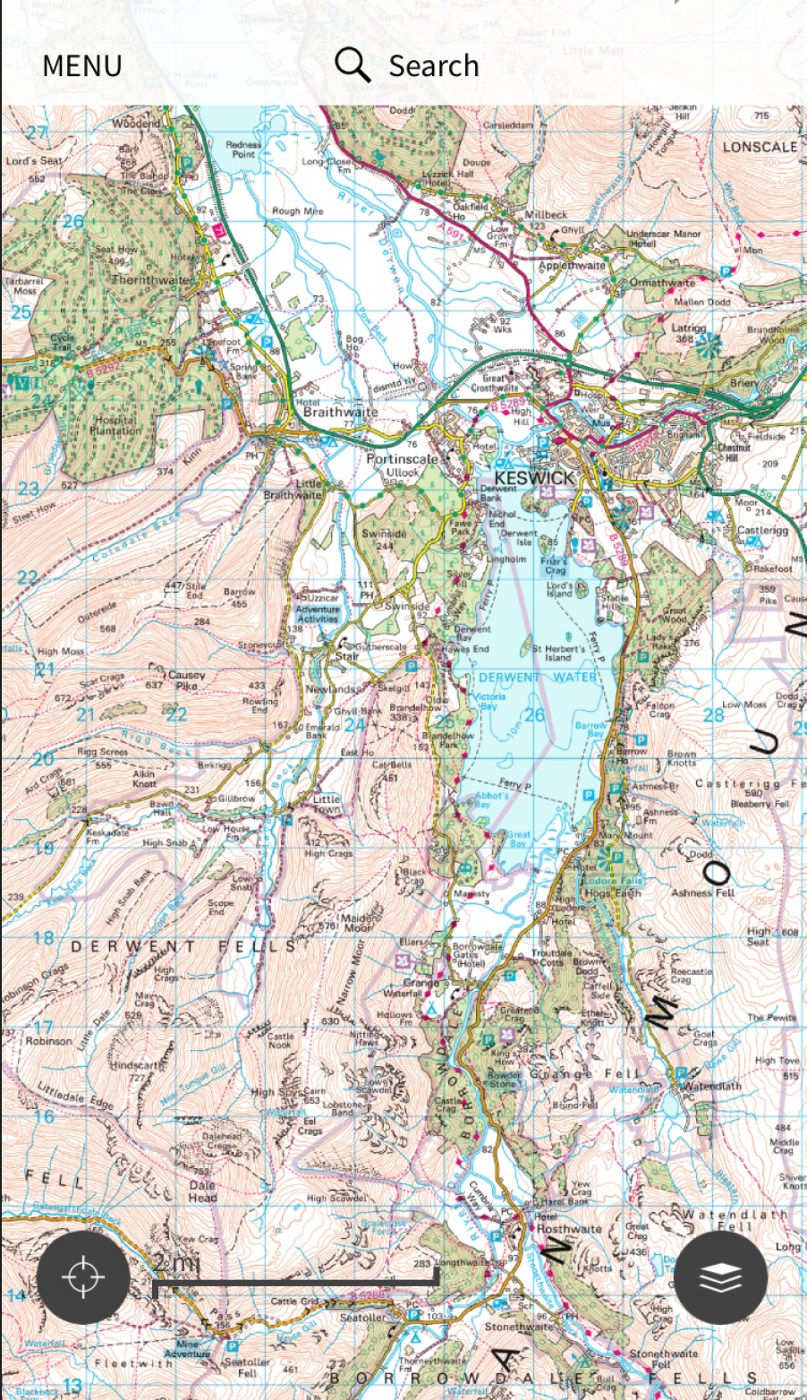

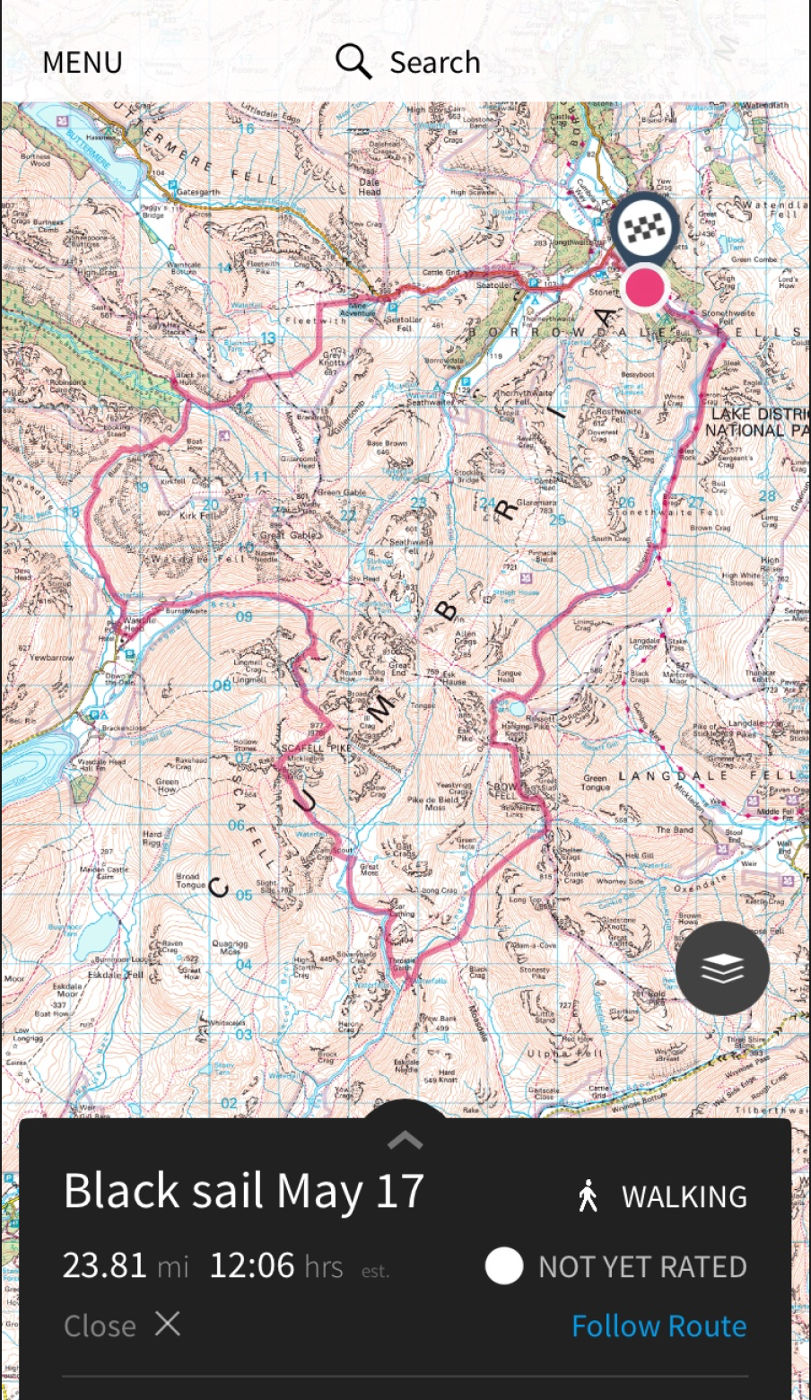

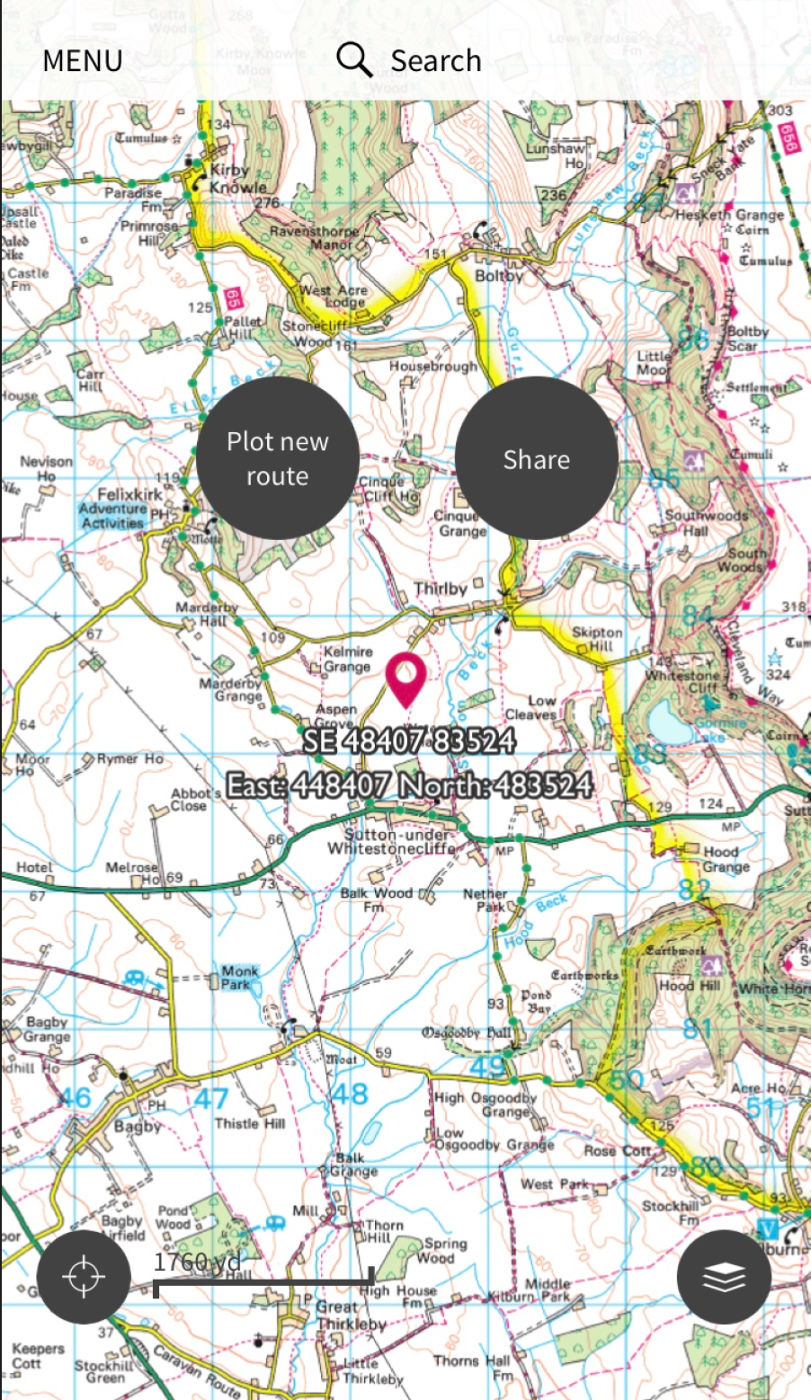

It’s better to be safe than sorry. Just because this post makes it seem easy doesn’t mean that it will be. You should take a fully charged mobile phone but this alone is not enough. Take an OS map. Take a compass. Know how to use them and do not walk the path in poor visibility.

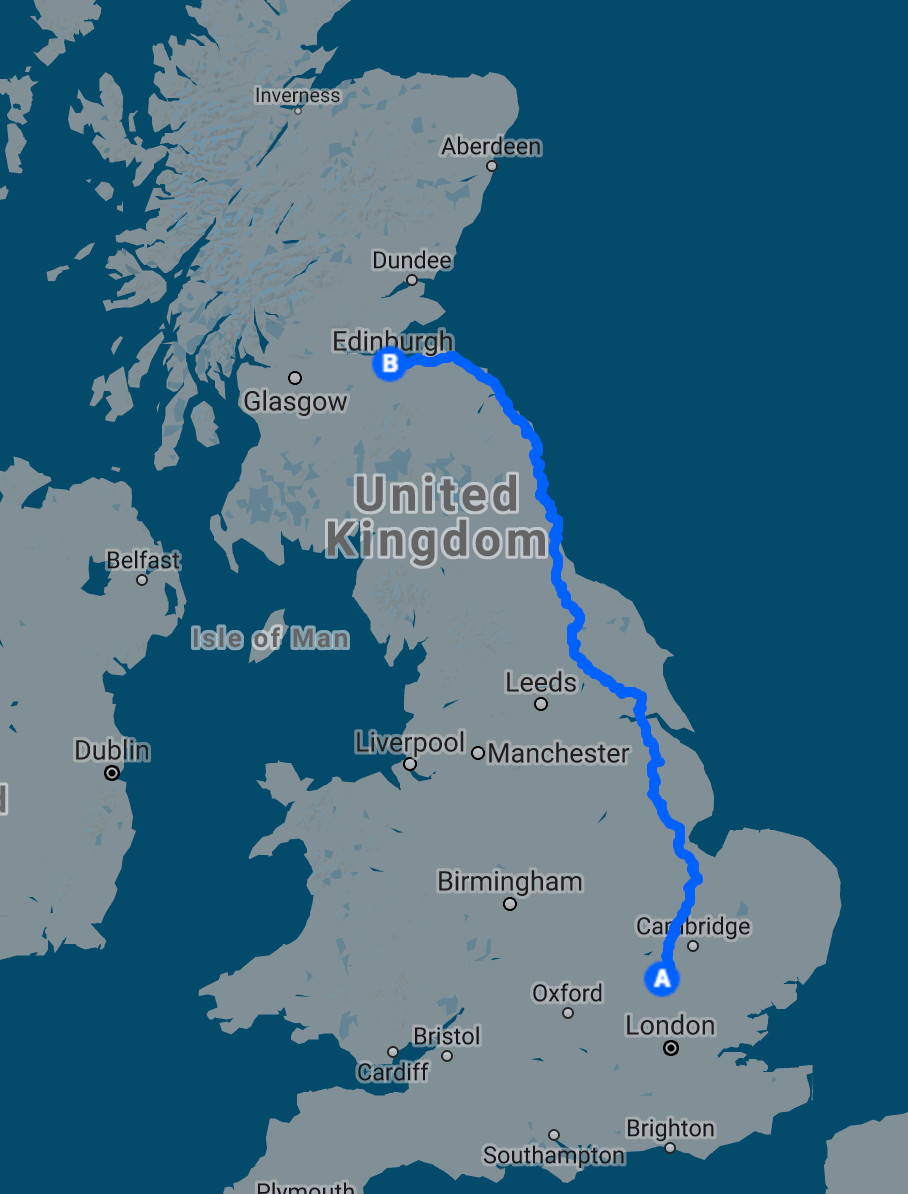

Stevenage train station, packed and ready for the 5 hour train ride to Edinburgh.

Stevenage train station, packed and ready for the 5 hour train ride to Edinburgh. The superb Forth railway bridge. I could at this point provide some highly dubious trivia, regarding how it’s always in the process of being painted, but I’ll spare you. The bridge I’m stood on in this picture, however, appears to be slowly falling apart. They have installed acoustic listening devices on the suspension cables to listen for the pings of breaking strands of steel, just to keep an eye on things. Reassuring.

The superb Forth railway bridge. I could at this point provide some highly dubious trivia, regarding how it’s always in the process of being painted, but I’ll spare you. The bridge I’m stood on in this picture, however, appears to be slowly falling apart. They have installed acoustic listening devices on the suspension cables to listen for the pings of breaking strands of steel, just to keep an eye on things. Reassuring. What’s great about Scotland is that you can camp anywhere, more or less. On my first night I found a quiet and secluded meadow that looked perfect. The sky was clear and the stars were out so I opted for the bivvy bag - wild camping at it’s best if you ask me! However, what I had failed to realise was that this meadow was part of an active construction site. The sound of reversing sirens are a lot louder than the alarm on my phone and went off quite a bit earlier too! An exchange of thumb’s-up was had and I was soon on my way.

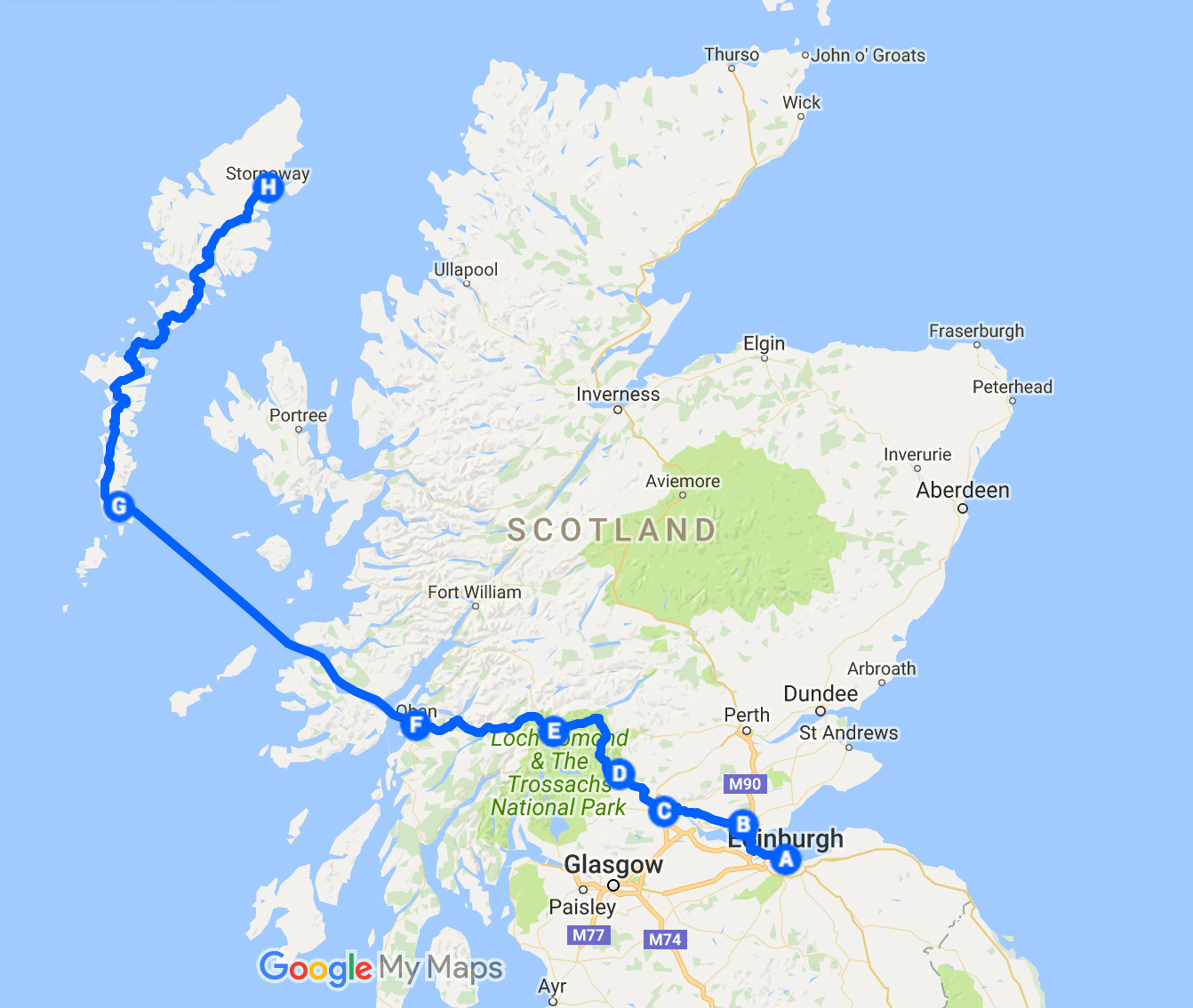

What’s great about Scotland is that you can camp anywhere, more or less. On my first night I found a quiet and secluded meadow that looked perfect. The sky was clear and the stars were out so I opted for the bivvy bag - wild camping at it’s best if you ask me! However, what I had failed to realise was that this meadow was part of an active construction site. The sound of reversing sirens are a lot louder than the alarm on my phone and went off quite a bit earlier too! An exchange of thumb’s-up was had and I was soon on my way. I’m sure by this point you’re beginning to see that the main character of my trip was my trusty steed, Honky. What I don’t have, sadly, is many pictures of all the people I met on the way. Whilst heading through the Highlands towards Oban I met Colin from Wyoming who had been travelling across Europe and was on his final leg, cycling in Scotland. We were headed in the same direction for the next 50 miles or so, so we buddied up for the day. We stayed at a campsite that night and enjoyed a good night’s drinking down the local. The next day, a little sore-headed, we bid each other farewell and went on our separate ways.

I’m sure by this point you’re beginning to see that the main character of my trip was my trusty steed, Honky. What I don’t have, sadly, is many pictures of all the people I met on the way. Whilst heading through the Highlands towards Oban I met Colin from Wyoming who had been travelling across Europe and was on his final leg, cycling in Scotland. We were headed in the same direction for the next 50 miles or so, so we buddied up for the day. We stayed at a campsite that night and enjoyed a good night’s drinking down the local. The next day, a little sore-headed, we bid each other farewell and went on our separate ways. From Oban it was a 5 hour ferry ride to Lochboisdale, which I spent with a fellow cycle tourer; an Aberdeen girl who was headed for Barra. The boat ride had it’s up’s and down’s, every 15 seconds or so, in a relentless swaying motion. I have never seen so much vomit. My companion had assured me she’d inherited an iron stomach from a long line of seafarer’s, the look on her face as she slowly made her way through the ferry canteens mac’n’cheese told a different story.

From Oban it was a 5 hour ferry ride to Lochboisdale, which I spent with a fellow cycle tourer; an Aberdeen girl who was headed for Barra. The boat ride had it’s up’s and down’s, every 15 seconds or so, in a relentless swaying motion. I have never seen so much vomit. My companion had assured me she’d inherited an iron stomach from a long line of seafarer’s, the look on her face as she slowly made her way through the ferry canteens mac’n’cheese told a different story. I arrived on the Western Isles shortly after 11 to a pitch-black night. I put my lights on and cycled into the night. This was to be one of the best rides of my life, in complete darkness surrounded by the ethereal whirring of burrowing Puffins and the whistling wind. I cycled for a long way into the night until a car pulled up next to me. I was certain I had met my final bloody fate. The window of the car wound down and before appeared not an axe-wielding maniac looking for nocturnal cyclists but a friendly faced middle-aged woman. She asked me where I was headed, to which I replied ‘that way’, to which she said ‘there isn’t anything that way’. She recommended that I find a camp spot soon before heading into what was just squidgy swamps and pools for miles. She drove on and I set my bivvy up in the bus shelter a few yards up the road. This, unsurprisingly a poor place to camp, as I was the unwelcome visitor to what was already the home for every creepy crawly in the local vicinity. The morning light came as a relief. It also revealed my environment for the first time. A sparse, mostly treeless landscape with short rugged hills and endless tiny lochs.

I arrived on the Western Isles shortly after 11 to a pitch-black night. I put my lights on and cycled into the night. This was to be one of the best rides of my life, in complete darkness surrounded by the ethereal whirring of burrowing Puffins and the whistling wind. I cycled for a long way into the night until a car pulled up next to me. I was certain I had met my final bloody fate. The window of the car wound down and before appeared not an axe-wielding maniac looking for nocturnal cyclists but a friendly faced middle-aged woman. She asked me where I was headed, to which I replied ‘that way’, to which she said ‘there isn’t anything that way’. She recommended that I find a camp spot soon before heading into what was just squidgy swamps and pools for miles. She drove on and I set my bivvy up in the bus shelter a few yards up the road. This, unsurprisingly a poor place to camp, as I was the unwelcome visitor to what was already the home for every creepy crawly in the local vicinity. The morning light came as a relief. It also revealed my environment for the first time. A sparse, mostly treeless landscape with short rugged hills and endless tiny lochs. Loved these signs, at a glance it looks like a dinosaur, Nessie even. Kept my eyes peeled for otters (and Nessie) but had no such luck.

Loved these signs, at a glance it looks like a dinosaur, Nessie even. Kept my eyes peeled for otters (and Nessie) but had no such luck. These two french cyclists had spent the previous two days cycling together and went their separate ways not long after this picture was taken but not before sharing a wee dram of whisky and baileys too, plus a few tokes on our new friend’s jazz cigarette. Afterwards we all had a go at riding about recklessly on his recumbent bike, attempting to do skids in the middle of an A-road.

These two french cyclists had spent the previous two days cycling together and went their separate ways not long after this picture was taken but not before sharing a wee dram of whisky and baileys too, plus a few tokes on our new friend’s jazz cigarette. Afterwards we all had a go at riding about recklessly on his recumbent bike, attempting to do skids in the middle of an A-road. This is the Youth Hostel on the island of Berneray. On the way I passed by a village hall with a free wifi and by this point internet and phone signal had become a luxury, so I headed inside. I was met by an English couple. I politely asked if I could have the password, ‘Of course you can dear’ the lady said, ‘would you like to learn about the island’s history first?’, if only I had the courage to say no. I patiently leafed through binders of sepia photographs of stern faced school masters, fishermen, and priests, only to be told after a long history lesson that the internet was in fact down. Great! ‘But don’t worry,’ she said, ‘between you and me, the B-and-B down the road has a Wifi network with no password.’ I promised to keep my word and headed to the b-and-b, where sure enough I got some slow but usable free Wifi.

This is the Youth Hostel on the island of Berneray. On the way I passed by a village hall with a free wifi and by this point internet and phone signal had become a luxury, so I headed inside. I was met by an English couple. I politely asked if I could have the password, ‘Of course you can dear’ the lady said, ‘would you like to learn about the island’s history first?’, if only I had the courage to say no. I patiently leafed through binders of sepia photographs of stern faced school masters, fishermen, and priests, only to be told after a long history lesson that the internet was in fact down. Great! ‘But don’t worry,’ she said, ‘between you and me, the B-and-B down the road has a Wifi network with no password.’ I promised to keep my word and headed to the b-and-b, where sure enough I got some slow but usable free Wifi. Every hosteller’s worst nightmare: the axe-murderer, seen here moments before dealing the fatal blow. Thankfully this was not a real axe murderer but a fellow friendly traveller. That night there were a few of us staying in the old white-washed croft. Later in the evening a crusty old pirate-looking fellow turned up asking us if we wanted to buy some crab meat. Two young, and mute (up to this point) Italian sisters, looking a bit bewildered by their situation, piped up and took some of the crab from the man’s hamper. They had, however, misunderstood that the man would be expecting some recompense for his efforts and wasn’t just driving around doling out crab for nothing and so they shyly returned the crab. The man got very angry and huffed loudly the words ‘fucking timewasters’ before slamming the door, leaving his Jack Russell staring out through the window as his master trundled off in his old Rav4. It was scary, and we suspected he may be our axe-murderer. In the end his dog wandered off and we all woke up with the standard number of limbs.

Every hosteller’s worst nightmare: the axe-murderer, seen here moments before dealing the fatal blow. Thankfully this was not a real axe murderer but a fellow friendly traveller. That night there were a few of us staying in the old white-washed croft. Later in the evening a crusty old pirate-looking fellow turned up asking us if we wanted to buy some crab meat. Two young, and mute (up to this point) Italian sisters, looking a bit bewildered by their situation, piped up and took some of the crab from the man’s hamper. They had, however, misunderstood that the man would be expecting some recompense for his efforts and wasn’t just driving around doling out crab for nothing and so they shyly returned the crab. The man got very angry and huffed loudly the words ‘fucking timewasters’ before slamming the door, leaving his Jack Russell staring out through the window as his master trundled off in his old Rav4. It was scary, and we suspected he may be our axe-murderer. In the end his dog wandered off and we all woke up with the standard number of limbs. The next day I arrived on the Isle of Harris famous for it’s tweed. In fact, the Isle of Harris and the Isle of Lewis are indeed the same island, the only thing separating them being their geography, Lewis is largely flat and bleak, and Harris has some large, more Highland-like hills and mountains. You can see in the picture here a glimpse of the Hebrides’ famous white sands and aquamarine seas. If I could do this again I would allow myself more time to explore the beautiful beaches here.

The next day I arrived on the Isle of Harris famous for it’s tweed. In fact, the Isle of Harris and the Isle of Lewis are indeed the same island, the only thing separating them being their geography, Lewis is largely flat and bleak, and Harris has some large, more Highland-like hills and mountains. You can see in the picture here a glimpse of the Hebrides’ famous white sands and aquamarine seas. If I could do this again I would allow myself more time to explore the beautiful beaches here. It took me a long time to get back on the road after staying at the youth hostel in Rhenigidale, partly because it served such luxuries as this wood-burning stove and a DAB radio, but mostly because I knew would have to cycle up and over a mountain I had to cycle over to get here.

It took me a long time to get back on the road after staying at the youth hostel in Rhenigidale, partly because it served such luxuries as this wood-burning stove and a DAB radio, but mostly because I knew would have to cycle up and over a mountain I had to cycle over to get here. Aforementioned mountain.

Aforementioned mountain. The next day took me to Stornoway where I spent the night in an overpriced hotel, ate pub food, drank beer, and watched TV. The journey across Lewis had been bleak with really not much to speak of other than the brief glimpse of a White-tailed Eagle. The next day I took the ferry to Ullapool, the crossing taking us past the pointed peaks of Skye and I offering sightings of dolphins as they leaped from the water beside the boat. I loaded my bike on to the bike bus in Ullapool which took me to Inverness where I was to catch the sleeper train back home the following day.

The next day took me to Stornoway where I spent the night in an overpriced hotel, ate pub food, drank beer, and watched TV. The journey across Lewis had been bleak with really not much to speak of other than the brief glimpse of a White-tailed Eagle. The next day I took the ferry to Ullapool, the crossing taking us past the pointed peaks of Skye and I offering sightings of dolphins as they leaped from the water beside the boat. I loaded my bike on to the bike bus in Ullapool which took me to Inverness where I was to catch the sleeper train back home the following day. Dusk in Inverness on the final night of my trip. When I arrived at the station I was informed that there was no room for my bike on the train by an officious train guard standing in front of the mile-long Caledonian Sleeper train and that a courier would be driving it in a van to London. My whole experience on the sleeper was pretty dismal to be honest and I glad when it was over. Back in London I waited on a back street near Euston for a white van to turn up with my bike. A different man arrived from the one I’d handed my bike to in Scotland, and an hour late at that. My annoyance was neutralised when I noticed he’d made his part of the journey through the night with his young child sleeping in the front of his van, I thanked him and cycled to Kings-Cross where I caught the train home.

Dusk in Inverness on the final night of my trip. When I arrived at the station I was informed that there was no room for my bike on the train by an officious train guard standing in front of the mile-long Caledonian Sleeper train and that a courier would be driving it in a van to London. My whole experience on the sleeper was pretty dismal to be honest and I glad when it was over. Back in London I waited on a back street near Euston for a white van to turn up with my bike. A different man arrived from the one I’d handed my bike to in Scotland, and an hour late at that. My annoyance was neutralised when I noticed he’d made his part of the journey through the night with his young child sleeping in the front of his van, I thanked him and cycled to Kings-Cross where I caught the train home.